Gaming Climate Change

An Analysis of Climate Change Education Games with Speculative Game Storyboard | April 2022

Intro

Climate change is one of the most pressing global issues of our time, with indisputable ties to human consumption and waste. Countless scientists, activists, and global organizations have called for drastic action in response to climate change (Nations, n.d.), yet global emissions and waste have continued to increase (US EPA, 2016). The alarming realities of climate change beg the following questions: Are we doing enough to teach people about climate change and its consequences? What methods of teaching will lead to greater empathy, intersectional understanding and proactive action? As global change scholar Gilbert Ahamer has boldly proclaimed, humanity will need to game – not fight – climate change as a long-term strategy (2013). In this paper I will present my findings on climate change education and gaming, as well as suggestions for a game that will teach a broad youth and young adult audience about climate change.

Paper Excerpts

-

A simple search of “climate change education” yields vast results for both scholarly and popular discourse, but substantive reviews of scholarly literature on the topic seem fairly recent. Since climate change education focuses on the phenomenon of climate change, I did not peruse surveys of broader “environmental education.” As Stevenson, Nicholls and Whitehouse eloquently explain in their 2017 article, “in essence, climate change education is about learning in the face of risk, uncertainty, and rapid change.” Climate change education is meant to, ultimately, not just inform, but also preparing learners for the rapidly changing future and how to respond to it (Stevenson et al., 2017). Three key literature reviews on this topic stand out for their comprehensive survey of climate change education, as well as centering of young people and indigenous knowledge.

In their 2019 review, Monroe, Plate, Oxarart, et al., identified common themes in broader environmental education articles, such as a focus on personally relevant information and use of active teaching methods. Furthermore, educational literature with a specific focus on climate change revealed the following themes: “(1) engaging in deliberative discussions, (2) interacting with scientists, (3) addressing misconceptions, and (4) implementing school or community projects” (Monroe et al., 2019). The constructivist, hands-on, and individualized characteristics of these themes demonstrate attempts to help learners make sense of a seemingly distant phenomenon and cultivate positive habits. Despite the use of engaged teaching methods, several studies illustrate how the preponderance of curriculum relying solely on scientific knowledge-based approaches have been “largely ineffectual in affecting the attitudes of and behavior of children and young people toward climate change” (Rousell & Cutter-Mackenzie-Knowles, 2020). Monroe, et al. and a 2020 review by Roussell and Cutter-Mackenzie-Knowles both conclude with the same finding – very few educational programs activated learners as “practical visionaries,” capable of imagining a better future and then taking action to realize that future (Kagawa & Selby, 2010).

Roussel and Cutter-Mackenzie-Knowles make more explicit recommendations with the findings of their review, calling for more “participatory, interdisciplinary, creative, and affect-driven approaches to climate change education” in partnership with children and young people (2020).

Young people are regularly exposed to “apocalyptic visions” of the future through film, social media and the internet, resulting in existential anxiety (Rousell & Cutter-Mackenzie-Knowles, 2020; yet according to both reviews climate change education literature rarely addresses the emotional impact of this exposure. Thus, another important argument emerges: the need for more collaborative and learner-centered approaches that more “directly involve young people in responding to the environmental, social, and cultural complexities climate change” (Rousell & Cutter-Mackenzie-Knowles, 2020) with consideration of their emotional state.

The aforementioned reviews present their findings from a first-world viewpoint and prioritize Western literature, while Mbah, Ajaps, and Molthan-Hill use a post-colonial theory lens in their survey to highlight indigenous peoples’ agency and indigenous knowledge systems (IKS) throughout the developing world. The post-colonial lens acknowledges that historic colonization of developing countries amounted to cultural and “epistemic violence” (Spivak, 2003), marginalizing IKS and privileging Western knowledge, customs and culture. Through their prioritization of IKS in literature, Mbah, et al. identify the importance of social adaptation, structural adaptation, and institutional adaptation in IKS-based climate change strategies. In their review, they share how indigenous strategies can be used to decolonize climate change education through “critical, place-based, participatory, and holistic methods” integrated with existing science-based approaches (Mbah et al., 2021). Climate change education presents a crucial opportunity to integrate IKS, restore indigenous dignity, and privilege contextual, culturally-informed understandings (Mbah et al., 2021). This approach, driven by dialogue, mutual respect and shared knowledge can be more effective on a global scale, by including and supporting those who are least responsible for climate change, yet will suffer the most from its impact (Davis & Caldeira, 2010).

-

More than a decade ago, Stephens and Graham argued that climate change education should exist beyond formal education settings, since “the vast majority of people will engage with the issue of climate change outside of the traditional classroom” (Monroe et al., 2019; Stephens & Graham, 2008). Gaming can provide a unique opportunity to harness the intrinsic motivation associated with informal learning to impress upon players the urgency of climate change, while teaching responsive policies and actions. Learning about climate change through gaming also responds to the calls by educators and activists for more creative educational approaches with a focus on critical and creative thinking, and capacity building that will unleash young people’s capabilities as “practical visionaries” for the future (Stevenson et al., 2017).

In order to understand and analyze the current landscape of climate change educational games, I read scholarly articles about climate change and educational gaming and tested two games and a gamification app. With each game and the app, I asked the following questions:

What mode of teaching is being used? Simulation? Gamification? Problem-based learning?

Can it meet the complex learning goals for a complex topic?

Is this game or gamification approach effective?

What am I learning? What is the felt experience like?

Is it accessible?

See the hyperlinked images below to try the games for yourself!

-

In addition to the three games above, I also read several studies of climate change education and gaming. In this broader analysis of literature, I identified a few themes worth noting.

Most games either focus on individual decision-making or large-scale policy solutions. Few games provide an avenue to engage in both macro and micro level impact, as well as all levels in between (such as social or community level impact). Even in large scale studies, games were successfully utilized to study and influence individual consumption patterns over a 6 month period rather than integrating consumption habits and macro advocacy (Ro et al., 2017). Among the few exceptions I found in existing literature was Greenify, a game designed to teach adult learners about climate change (Lee et al., 2013), integrating individual action, peer network knowledge sharing, and learning about global impact.

Climate change games are not always accessible to broader audiences. Several games in the studies were board games or developed specifically for formal educational environments. Keep Cool, a German board game created for use in higher education, is a good example of an educational game created to be a “common language” among learners (Eisenack, 2013; Meya et al., 2018). The evidence of its success among students demonstrates the importance of games as mode of education, but also yielded a few caveats, such as lack of accessibility for young learners or informal learners, since the game cannot be played without supplemental information or curriculum. Keep Cool, which was once lauded as a successful, educational game, is no longer in production based on my research and searches. Greenify, a game that attempted to bridge the gap in real-world action amongst climate change games, is also unavailable on the internet.

Out of the 20 articles I read, very few gaming studies focus on affect or creativity. The literature reviews I referenced earlier in this paper specifically called for more interdisciplinary, affective, and creative educational opportunities, but most games and studies of educational climate change gaming are limited to teaching habits and raising awareness, rather than integrating or prioritizing creativity and affective learning. A Spanish study of climate change games found that games have a lesser impact on stimulating the “development of solutions and ideas through creativity,” with higher results of gaming case studies being increased familiarity with the topic and awareness of causes (Ouariachi et al., 2017). While awareness and increased familiarity are still valuable, engaging effect and creativity as a primary goal of climate change games will also increase empathy and could lead each player to take action in real life. The creative, world-building aspects of Eco certainly seems generative, but there is no scholarly study of the game at this point. Within scholarly literature, Greenify seemed to be an exception because it was created with the aim of cultivating personal relevance, positive peer pressure, and harnessing “generative power” (Lee et al., 2013). The game design involved Missions – practical actions for everyday life – and Exploration, ways to learn through a collective, interactive knowledge-sharing environment (Lee et al., 2013). Through pre- and post-surveys, players indicated they felt more empowered to do something; some players even comment that the interaction with other players and the social, affective component was the most powerful aspect of playing the game.

In my review of climate change gaming literature and analysis of climate change games, almost none prioritized culture or culturally-relevant solutions to climate change. This is a lamentable, large gap in the current landscape of climate change gaming, especially given the disproportionate impact of climate change on indigenous people and developing countries.

-

Utilizing the brief analysis of existing climate change gaming literature and a survey of climate change education, I was able to distill key principles for designing an accessible, relevant, and action-driven game.

Prioritize affective goals and creativity; help players be empathetic, practical visionaries

Prioritize narratives of hope and constructive action to negate existing feelings of anxiety and exposure to visions of apocalyptic futures

Integrate indigenous knowledge systems or culturally-informed narratives and solutions

Integrate individual, collective and macro level solutions

Prioritize accessibility; people should be able to play without high-end computers or paying high costs

Three Games About Climate Change

Click on the images to navigate to game sites.

Eco

“Eco is an online world from Strange Loop Games where players must build civilization using resources from an ecosystem that can be damaged and destroyed. The world of Eco is an incredibly reactive one, and whatever any player does in the world affects the underlying ecosystem (Eco - English Wiki, n.d.)” Eco is a complex world-building, server-based simulation game created for gamers. Given the predominant use of simulation in climate change research and the urgency of this global issue, scholars have pointed out the importance of simulation as a tool for teaching about the impact of climate change, policy solutions and also cultivating empathy among people (Crookall, 2013). Lauded for the involvement of scientists in its design, the accuracy of the climate models, ecosystems, and environmental impact data in the world of Eco bodes well for cognitive and behavioral learning possibilities (Lee, 2020).

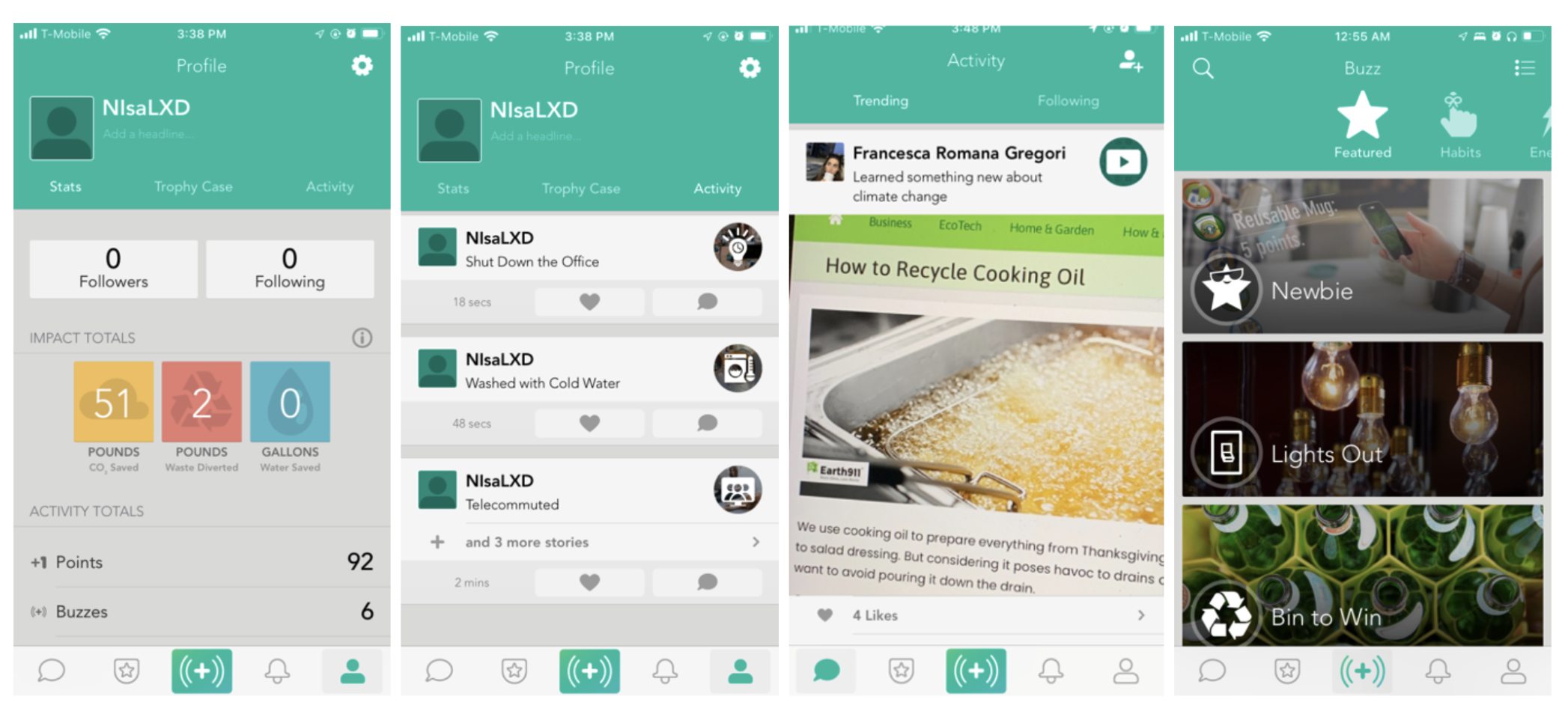

JouleBug

A mobile application that gamifies sustainable habits, JouleBug is described by its creators as an “easy way to make your everyday habits more sustainable, at home, work, and play” (About - JouleBug, n.d.).

The Climate Game: Can you reach net zero by 2050?

Launched by The Financial Times in 2022, The Climate Game offers a web-based simulation in which players attempt to “save the planet from the worst effects of climate change” (The Climate Game — Can You Reach Net Zero?, 2022). The goal of the Climate Game is to prevent drastic global warming by “cutting energy-related carbon dioxide emissions to net zero by 2050” by making policy decisions as the new Global Minister for Future Generations (The Climate Game — Can You Reach Net Zero?, 2022). The future of the planet relies on each decision made by players, with game play taking place over a span of almost three decades in the narrative. The planet changes in response on each decision and CO2 emissions are updated to show the impact.

WHat might we create an Accessible, empathy-centered, and impact-oriented game about climate change?

I challenged myself to create a game based on the aforementioned principles.

My game, titled “Inheritors of the Earth,” would be an AI-driven game played on a browser or on a mobile phone. In Inheritors players are able to communicate with their descendants 100 years from now and learn about the world they live in. Urged on by their descendants and future perils caused by climate change, players must act to shape a better future. Players can complete missions and tasks that build in complexity to earn points, improve the future, and even win sustainable prizes like a gift certificate to a local co-op. Players can accomplish tasks, upload pictures of their tasks, learn something new based on their interests, and see how their actions are improving the future as they complete them.

Empathy Map and Prototype Storyboard Available Upon Request